Now that the basic foundation of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism has been presented, it’s time to examine the potential similarities between that philosophy’s argument and the written work of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In particular, I will be focusing on a close reading of his essay Self-Reliance (1841). Again, like the post on Ayn Rand, I will begin with some contextual biographical information before describing and evaluating his work and its similarities to Rand’s. Before I continue I wish to reiterate that the purpose of this writing is not to insinuate that the total philosophies of Rand and Emerson are the same. The point is not to evaluate all of Objectivism and transcendentalism but rather to use a basic understanding of Objectivism as a lens through which to view specific works and make connections.

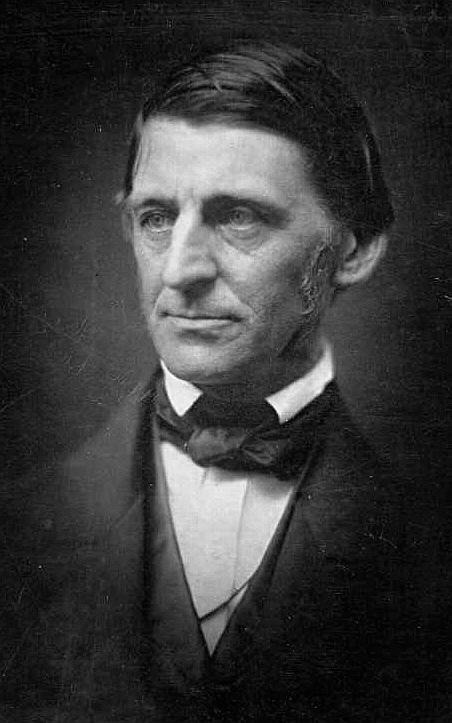

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American essayist, philosopher and lecturer born in 1803 in Boston, Massachusetts. Coming from a religious family, he was eventually ordained in the Unitarian church after graduating from Harvard (“Ralph Waldo Emerson”). However, Emerson later began to question his faith and eventually renounced his Christian doctrine altogether and resigned from the church (“Ralph Waldo Emerson”). Like Rand, Emerson came to the school of philosophy that would eventually become synonymous with his name, transcendentalism, through literature, specifically a personal manifesto called Nature (1836) (“Ralph Waldo Emerson”).

Self-Reliance, an essay written by Emerson in 1841, could be viewed as a tribute to individualism. The author advises his readers to resist conformity and live life according to his own perception and understanding in service of no one but himself. The centrality of individualism in Emerson’s work indicates a clear connection between him and Rand. According to the former, “No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution, the only wrong is what is against it,” (Emerson 238).

In this passage, Emerson constructs an understanding of the world that is centered entirely around the individual. The only natural law an individual is bound to respect is that of his own nature, and there is no moral code or concrete understanding of what is good or bad that comes from outside that individual that he must observe. This line of thinking is strongly connected with Rand’s Objectivist notion of the morality of self-interest. Rand wrote, “Man — every man — is an end himself, not the means to the ends of others. He must exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself,” (4). Both authors advocate a worldview focused almost entirely on the individual self.

Another claim that binds Emerson and Rand is their understanding of the relationship between perception and reality. As previously mentioned, Rand’s Objectivism views perception as man’s only true source of knowledge and, therefore, a crucial part of his understanding of reality. Similarly, Emerson wrote of the supremacy of perception in Self-Reliance:

Thoughtless people contradict as readily the statement of perceptions as of of opinions, or rather much more readily; for, they do distinguish between perception and notion. They fancy that I choose to see this or that thing. But perception is not whimsical, but fatal. If I see a trait, my children will see it after me, and in course of time, all mankind, — although it may chance that no one has seen it before me. For my perception of it is as much a fact as the sun. (244)

Like Rand, he wrote of perception not as a subjective interpretation of reality, but as reality itself according to the law of the individual.

Works Cited:

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Ralph Waldo Emerson.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 May 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/Ralph-Waldo-Emerson.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Self-Reliance.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature, 9th ed. Robert S. Levine, editor. W. W. Norton, 2017. pp. 236-53.

Rand, Ayn. The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought. NAL, 1988.